You are currently browsing the daily archive for August 1, 2015.

The following is the oral presentation I gave at the University of Ottawa”s “Celtic Chair Lecture Series” on November 8th, 2012.

“Skellig Michael: A Desert In the Ocean” by (Brendan) Rob O’Gorman.

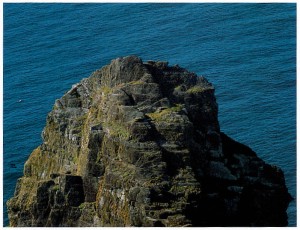

About seven miles off the ‘Ring of Kerry’ off the southwest coast of Ireland, there are a pair of islands known generically as ‘the Skelligs’. The smaller of the two is a wild bird sanctuary, containing up to 25,000 mating pairs of birds. The larger of the two has become associated with the Archangel Michael, and is popularly known as “Skellig Michael”. But it has not always gone by this name, for in the late 6th/early 7th century, a group of Irish ascetics (monks) established themselves here – for them it was known as ‘Sceilig Figil’ or translated, Ocean-Rock Vigil (or Prayer). It is not difficult to see why, for the entire island is one of verticality, constantly drawing the eye upwards toward the Heavenly Realm. For many, this was their ‘place of resurrection’ a final place of rest, before departing this temporal (earthly) world for another heavenly one. It was no doubt Skellig’s ‘otherworldly’‘ quality that lead the Irish writer George Bernard Shaw to exclaim: “I tell you, [Skellig] belongs to no world that you and I have ever lived and worked in! It is part of a dream world… Whoever has not stood in the lacht [graveyard] on the summit of that cliff, among the beehive dwellings and their beehive oratory, does not know Ireland through and through…”

In order to understand the impetus for these monks to settle there, we’ll need to step back a few centuries… In the years after Christ’s death and resurrection, His ‘Good News’ (or Gospel) spread throughout the eastern, then western Mediterranean regions, into such places as North Africa (eg. Egypt). But the early church was a persecuted one, and countless individuals and groups paid for their allegiance to Jesus Christ with their lives! Yet by the third century, Rome’s Empire had become more tolerant of many religions and beliefs; thus, with the ‘Edict of Toleration’ in 315 AD, Celestine formally/officially ended the persecution of Christians. Moreover, he further decreed that Christianity was to become the new ‘state religion’. Those who had any aspirations in the new Roman Empire quickly understood that to realize any of their plans, one had to ‘get with the program’ as it were, and become Christians, if only in name. Not surprisingly, many saw this as a cheapening (watering down) of the true Gospel message. Before this event it was Paul of Thebes who fled the persecutions of Christians under Decius and Valerianus in 250 AD and remained there until he died in 341 AD. Another man of the desert wasAnthony (The Great) who elected to emulate the 40 days of Christ’s temptation in the desert, and to engage in ‘spiritual combat’ for the salvation of his soul. With the end of the blood persecutions of Christians, renouncing the world and withdrawing to the desert became a new form of martyrdom. The accounts of these desert dwellers were written down by Athanasius, and subsequently fired the imagination of many (especially young men) in Ireland.

Meanwhile, in the rest of the world, Christianity began percolating west and north into Gaul (France) and possibly the British Isles and parts of Ireland. In fact, no one really knows when Christianity arrived in Ireland, though trading across the ocean (eg. Loire Valley of France) is immediately suspect. Some early medieval sites have unearthed wine pots etc., from as near the Loire Valley, and from as far away as North Africa. So, however it happened, there were likely small enclaves of Christians living in the ‘Emerald Isle’ for some time. Of course, Patrick arrived in 433 AD and set about his efforts to evangelize the Irish, usually beginning with the Kings & Chiefs. Having studied in Gaul, Patrick would likely have been aware of the so-called ‘Desert Fathers’ through Athanasius, but his vision of the church was to be based on theparuci/diocese concept. Upon his death, the Irish set about developing their own style of monasticism, base on their own indigenous tribal customs. And here is where things get interesting! Amongst contemporary discussions surrounding Celtic Christianity, or the Christianity of the early Celts, experts unanimously support the fact that one of its most important features is that it was, in fact, monastic!

And it may be useful to digress for a moment to consider what connotations ‘monasticism’ has in popular culture. To be sure, these include robed figures, gliding amongst cloistered abbeys, with the usual collection of refectories, scriptoriums etc. Monks (or nuns) would renounce the world, entering a life-long commitment to serve Christ, and adhere to the tripartite emphasis on poverty, chastity and obedience. As well, and especially in the Benedictine tradition, amongst the solemn vows is one of ‘stabilitas’ – remaining in that one place until the day of your death. This was the Roman/Continental form of monasticism.

Not so for the Celtic form of monasticism. Here the Abbot (not the Bishop) held sway over single-sex monastic communities, and in some cases monasteries of both men and women. These monasteries were often set in astonishingly beautiful locations, where individuals could work out their salvation in peace and tranquility Unlike the conforming nature of the continental monastic orders, the Celtic monasteries were each different from each other (nearly anarchic), reflecting the Celtic approach to familia, and the individual temperament of the founder. Each was governed by a founder’s ‘Rule’, and were sites of great hospitality to the poor, places of refuge for criminals, while others were great centres of learning, while others were mission centres etc.. Though their monastic practices reflected great diversity in terms of its set-up and other externals, they nonetheless operated in spiritual unity with the One Holy Church. Like the Desert Fathers and Mothers before them, their model of being was centred on Prayer, Work and Study. If all of this seems a bit settled, this would change with their understanding of what penance was. For the Celtic monks the ‘desert’ was not so much a place that fitted the hot/dry landscapes of north Africa, but as a place of promise and fulfillment – a place where an encounter with God was not only possible – but even pursued.

To facilitate this, the early Celtic monks had their own (three-fold) manner of penitence (metanoia – ‘turning around), and heralding the emergence of two (2) new (bloodless) martyrdoms.

– Red Martyrdom – death for the sake of following Jesus Christ – which would soon happen with the Viking’s arrival

– Green Martyrdom – To put oneself under all manner of denial & deprivation (eg. fasting, vigils, imposed silence)

– White Martyrdom – To engage in self-exile (leaving one’s homeland, never to return) a concept nearly unthinkable to the Irish mind – a supreme act of self-abnegation. The result of this led theCeltic Monks to be propelled to the status of ‘Super-Hero’, becoming the moral protagonists of their time. Young men in particular, eager to engage in this new ‘spiritual combat’, flocked to the monasteries in droves.

But what was the impetus for these early Christian monks, to sojourn out to such wild and seemingly inhospitable places? The answer to this puzzle is multi-faceted:

– Irish Folklore/Law – Cen Immram, for killing of family members, person was cast adrift with feet secured. If they survived, they were innocent, if not – they were guilty of their crime.

– ‘White Martyrdom’ – persecutions of Christians end, but a new (bloodless) martyrdom

– ‘Peregrinatio’ – Explicit/implicit meaning – Pilgrim, Self-exile, Stranger (like the Desert Fathers, they were ‘resident aliens’, no place on earth is ‘home’. Like Jesus’ life, they had no place to lay their head (Matt 8:20).

Read/Insert Irish poet Kerry Hardie’s poem ‘Skellig Michael’.

In emulating these earlier Christians, the Celtic monks developed a peculiar way of seeking God from their island landscapes, or their “desert in the ocean” if you will. While their eremetical existence could often be extreme, some Irish monks further sought to emulate Christ’s life in another way, notably in pursuit of ‘theosis’ (deification) via journey or pilgrimage. In considering many quotes from the Holy Scriptures advocating self-renunciation, they incorporated an interesting aspect which Esther De Waal describes as:

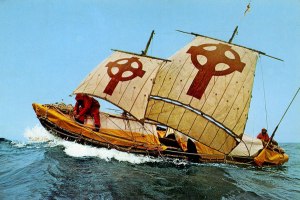

“seeking, quest, adventure, wandering, exile – it is ultimately a journey … to find the place of my resurrection, the resurrected self, the self that I might hope to be, to become, the true self in Christ. The journey is possible only because I am finding my roots – that familiar paradox known in all monastic life and a reflection of basic human experience …in the place in which finds oneself…” (Photo Further Below: Tim Severin’s own ‘Brendan’ voyage (with an identically constructed craft) that successfully demonstrated Brendan’s ability to reach North America some 500 years before the Vikings!)

This Irish concept, called peregrinatio, is both striking and profound. De Waal declares that the term is found “nowhere else in all of Christendom”, also warning that the word is almost “untranslatable”. It consisted of a willingness to let go of or die to one’s home, or the place that was comfortably familiar, in order to find new life. Accounts of their Otherworldly voyages, such as that found in theNavigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis (The Voyages of Brendan The Navigator) seem to typify a desire on their part to marry a bleak, and apparently barren, outer landscape with their inner landscape (inscape), all the while searching for the elusive “promised land” (paradise). Commenting on these Celtic monk’s need to travel in search of a spiritual goal, one author states:

“I think that the idea of journey and travel and movement takes on a particular passion and longing when you realize that … even though these Celtic [saints] wandered, their wandering was never a growing in distance from the spirit or spirituality, but in some way a coming closer to it.”

Most assuredly, their intentions and motivations cannot be reducible to that of purely penitential practices. There is simply too much mystery here. As John Finney makes clear, “their spirituality was that of those on the edge. They were groupings of Christians clinging onto faith at the edge of the known world. It is a spirituality and theology of the insecure…”

Skellig Michael (Historic Origins of The Monastery)

The first reference to the Skellig’s occurs in legend when it is given as the burial place of Ir, son of Milesius, who was drowned during the landing of the Milesians. A text from the eighth or ninth century refers to an episode of strife between the Kings of West Munster and the Kings of Cashel. Duagh, King of West Munster is said to have ‘fled to Scellecc’. This event is attributed to the fifth century – but (for the moment) we have no means of knowing if a settlement existed on the island at that time.

Skellig monastery may have been founded as early as the sixth century, reputedly by Saint Fionán, but the first definite reference to monks on the Skelligs dates to the eighth century when the death of ‘Suibhni of Scelig’ is recorded. Skellig is referred to in the Annals of Innisfallen in the ninth and tenth centuries and its dedication to Saint Michael the Archangel appears to have happened some time before 1044 when the death of ‘Aedh of Scelic-Mhichíl’ is recorded. It is probable that this dedication to Saint Michael was celebrated by the building of Saint Michael’s church in the monastery. The church of Saint Michael was mentioned by Giraldus Cambrensis in the late twelfth century. His account of the miraculous supply of communal wine for daily Mass in St. Michael’s Church implies that the monastery was in constant occupation at that time.

But what would life on such an apparently desolate and inhospitable island like Skellig Michael have been like? To be sure, accessing the islands from the rough, and often turbulent North Atlantic would be nearly impossible. To overcome this,the monks established three (3) landing points on the island, dependent upon the state of the sea. They quarried readily available rock slabs and painstakingly established hundreds of steps up to their monastic site.

The only route still in use today is the ‘Southern’ route, accessible by boat landing in Blind Man’s cove. Other practical necessities had to be addressed, such as food and water. To satisify their hunger, the ocean around was plentiful of fish. There were also sea-bird’s eggs and the birds themselves, including manx Shearwater and storm petrels, fulmar, kittiwakes, guillemot’s and puffins (8 months), whose underground burrows provide no end of joy!

Finally, there is evidence that some supplies were brought from the mainland, including wine, porridge and other sundries, suggesting an early connection to a nearby monastery.

And while the Skellig monks ate reasonably well, water was a critical problem. The island has no fresh water spring/supply, and without fresh water, the monks could not have stayed on Skellig. Fortunately, if there is one thing that Ireland gets in abundance, is rain! The monks ingeniously created a series of ledges etc., to direct rainwater to an underground cistern which held up to 500 litres of waterin a centralized location.

Daily life for the monks on Skellig would have been centred around prayer. Communal prayer would have been carried out at the cardinal points of the day (and night), such as lauds, vespers, compline etc., and the monks would have integrated many of the practices of the Desert Fathers, including fasting – esp on Wednesdays and Fridays – but also fasting from speech, for silence was an integral part of the monastic life – to live in communion with God!

Apart from prayer would be the daily work of excavating stone for their shelters, oratories, walls and innumerable steps from the three access points to the main monastery itself. Incredibly, for some, even these measures to cultivate solitude and stillness were not enough! For on the south peak, a small one-man cell was established, the only way of accessing it was up a steep and terrifying climb to a point above, where a small hermitage with a commanding view of the area was established. For many, this was the ultimate contemplative experience – their last earthly ‘paradise’ before their departure for heaven/the otherworld.

But with the arrival of the Normans, and the influx of the continental style of monasticism, things were bound to change. It can be said that the ‘wildness’ of this expression of the early Celtic Church was being tamed, and regulated, giving way to the rules and conformity of Roman orders, such as the Augustinians. The thirteenth century saw a general climatic deterioration resulted in colder weather and increased storms. This, together with changes in the style and structure of the Irish Church, signalled the beginning of the end of the eremitical community on Skellig Michael. The Celtic monks appear to have moved to the nearby Augustinian Abbey at Ballinskelligs on the mainland about this time. Its Prior was referred to as the Prior de Rupe Michaelis in the early fourteenth century, implying that Skellig Michael still formed an important part of their monastery at that time.

Skellig Michael appears on a number of Italian and Iberian portolan charts of the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries and the accounts of the Spanish Armada show that the island was known to them in 1588. Around this same time, a dissolution of the monasteries decreed by Henry VIII, although the site continued to be a place of pilgrimage well into the nineteenth century. At the same time two lighthouses were constructed, and a road was built along the south and west side of the island to facilitate the construction of these structures on the west side of the island. By the 1880’s, the Office of Public Works took ownership and in 1996, Skellig Michael was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site (one of only three in the Republic of Ireland).

Quo Vadis? (Where To From Here)

This short presentation about Skellig Michael will no doubt generate more questions about the site and this early Celtic monastic movement – a movement which was, by its nature centrifugal as opposed to being centrifudal. It was a movement NOT towards the centre, but rather a retreat from it! It was a withdrawal to the margins of the then-known world, arguably at the end of time itself. Like Patrick himself believed, these monks were preparing for the imminent return of Jesus Christ. Their often severe penitential practices (such as cold water immersion) to ward off evil thoughts, their continual prayer and fasting was designed to empty themselves of SELF, allowing their EGO to be replaced by the movements of the Holy Spirit. They were ‘island soldiers’, transplanted onto the island to “take out” dark/enemy forces, and replace them with good/holy ones. One writer, David Adam, even went so far as likening them to the British SAS (special forces) – the tough guys (or commandos) of the early Christian Church! Whether this is true or not, one thing is certain – these Celtic monks, like the Desert Fathers before them, went to Skellig Michael, and did the things they did (fasting) in order to prepare for an experience of the Divine! What were they seeking, if not the Uncreated Love of God?!

So where does that leave us, mere mortals like you and me? Why are you here? Why am I? Hopefully not to hear me! Perhaps part of the answer can be found closer to home than we might think! Writing about the Canadian wilderness experience an eminent ethnographer once wrote that “we can best discover who we are by going to what we think of as the margins of our world”. There is something important about margins, and ‘edge’ places… And there is also something in ‘wild’ and seemingly inhospitable places that we need to live.

Elemental places like Skellig Michael are critically important to our spirit and our psyche. Such places are great ‘levellers’ and cannot be traversed hastily. In order to learn anything from such a place, one must go slowly (two people died in 2010 because they chose not to). There is very good reason why SOS (Save Our Souls) is not only a traditional mariner’s distress, but (I would suggest) a critical step towards an economy/ecology of spirit! In our fast-track, post- modern culture, many souls feel like flotsam (drift wood), having drifted ashore on something vaguely familiar, or altogether new. Perhaps Skellig Michael satisfies a religious/spiritual need that we all have to one degree or another – the age-old paradox, that in our ‘seeking’ we actually becoming ‘found’, in our quest for a more uncluttered faith, we might find simplicity.

Not surprisingly, such an adventure as this can be found in the early Irish voyaging (immrama) texts! And it is not surprising to find early stone oratories (churches) constructed in the shape of a boat, such as the Gallurus Oratory on the Dingle Peninsula (photo below). Even today, many cathedrals (such as the Orthodox one I go to) have a boat-like ceiling, giving the impression that upon entering, one is actually stepping into an Ark!

Like Skellig Michael, or any of the other Celtic monasteries, the pilgrim is on a journey with a spiritual goal in mind, giving credence to the old Irish saying that “it is better to travel hopefully, than it is to actually arrive”. Here, the genuine seeker finds a clear and compelling answer to their quest to find the perfect, holy and Uncreated love of God. (Brendan statue overlooking Fenit Harbour, where he was born.)

In the past few minutes, I have attempted to explore the spiritual legacy of Skellig Michael with you. I think that you will all agree with me that it stands as a testimony to all (both believers and unbelievers) of the resilience of the Celtic Christian tradition – which holds such profound significance to so many today. Thank You.

~ Written & Presented by (Brendan) Rob O’Gorman

Skellig Michael: A Desert in the Ocean

Topic: Situated some seven miles off the south coast of Co. Kerry Ireland, lies an ancient Celtic monastery popularly known as Skellig Michael. First established by Irish monks in the 6th century (and still venerated by countless pilgrims to this very day), this lecture will examine the religious, socio-cultural and phenomenological impetus which resulting in its creation/establishment. Join us for a 21st century odyssey into an early medieval expression of Irish spirituality!

Presenter: (Brendan) Rob O’Gorman is a writer, poet and lecturer who lives rurally near Almonte, Ontario. A graduate of the Celtic Christianity program via the University of Wales (Lampeter), his interests include studying ancient Celtic ‘adventure’ texts, early medieval poetry, and sojourning into such seemingly fierce and inhospitable landscapes as Skellig Michael (Sceilig Figil).

WHAT IS MINDFULNESS? (from Mary Ann Evans, 28 W. Arrellaga Street, Santa Barbara, California 805 689 0849)

“Mindfulness is paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment and non-judgmentally”. (Jon Kabat-Zinn)

Mindfulness allows one to experience each moment with clarity and serenity, no matter how difficult or intense the situation. This practice allows one to directly connect with what is happening moment by moment by gathering our attention around an object or sensation in order to be in touch with our experiences. By learning to pay attention to what is going on and starting with what “is”, then we can refine our attention in order to develop a relationship with what is happening without judging or expectations. It is not about what is happening, but about how we are with what’s happening. We develop the sensitivity to respond mindfully rather than react in an automatic fashion. Mindfulness gives us space to be with our experiences, to understand, accept and thoughtfully respond. This practice allows everything to come alive in the midst of our daily activities.

Benefits of mindfulness:

Feeling stressed, overwhelmed, anxious, facing a life crisis or illness or just longing to find a place of rest form the pace of modern life? If so, give yourself the gift of experiencing the peace of the present moment, deep states of relaxation and awaken to enjoyment of life’s simple pleasures. This is the gift of mindfulness. It reduces Stress, improves concentration, eliminates fatigue, enhances relationships, increases tolerance, increases creativity, reverses effects of aging, increases fullness of living.

WHAT IS MINDFULNESS BASED PSYCHOTHERAPY?

The most common forms of psychotherapy utilize discussion about life circumstances, emotions, beliefs and suffering. The therapist attempts to help the client understand the events of the past and how these effect current and future challenges. This approach may be effective for some people; but for many others it becomes very helpful to incorporate a practice of mindfulness with cognitive therapy. By utilizing mindfulness practice in psychotherapy the client learns how to increase awareness, bolster mood, reduce stress and find inner peace. By attending to the present moment the anxiety about the future and rumination of the past are reduced and life becomes fully, more joyful and meaningful. This approach, when used in psychotherapy, teaches skillful ways of navigating one’s inner landscape, which may produce stress, inattention, anxiety and depression. Using a variety of methods including meditation, cognitive therapy, body awareness, and group process, participants learn to train their minds and achieve deep levels of relaxation, self observation and emotional regulation.

RESOURCES

AUDIO FILES BY DR. MARY ANN EVANS – LIVING FULLY IN THE PRESENT MOMENT

Disc 1

- Welcome to the Present Moment

- Awareness of the Present

- Mindful Eating

- Mindfulness of Ordinary Moments

- Rumi ‘The Great House’

Disc 2

Disc 3.

Recent Comments